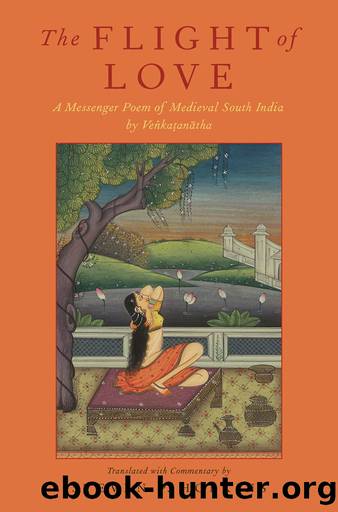

The Flight of Love: A Messenger Poem of Medieval South India by Venkatanatha by Steven P. Hopkins

Author:Steven P. Hopkins

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Published: 2016-03-31T16:00:00+00:00

VenÌkatÌ£eÅaâs Geocultural Imaginary: Stages of the Southern Route

RÄma then tells the goose in great detail where it is to go, across what beloved landscapes, to Laá¹ kÄ and to SÄ«tÄ. He imagines in vivid detail stages of the southern route, a geographical imaginaire that favors very specific southern regions that, though particular to this ÅrÄ«vaiá¹£á¹ava poet of northern Tamil Nadu, immediately bring to mind the literary Tamil landscapes described in Kampaá¹âs IrÄmÄvatÄram. Veá¹ kaá¹eÅa praises the Toá¹á¹ai, CÅḻa, and PÄá¹á¹iya regions, the exoticized charms of Andhra and Kará¹Äá¹ic girls (an idealized erotic ecology from the Tamil perspective), the KÄvÄrÄ« and TÄmrapará¹Ä« Rivers, the equally exoticized badlands of tribal forests, and the very few specific shrinesâTirupati, KÄḷahasti, VaradarÄja, and EkÄmreÅvara temples in KÄñcÄ«, the simple serpent shrine in the country in what will become ÅrÄ«raá¹ gam, Vá¹á¹£abha Hill, and its Anklet Gaá¹ gÄ, a landscape marked by particular beauties and the extravagant rhetoric of a loverâs awe.31 Veá¹ kaá¹eÅaâs South also gives reference to conventionalized landscapes (tiá¹ai) in old Tamil poetry, from the hill country of Tirupati (kuriñci), the wilderness (pÄlai) of the Kallar lands, to the CÅḻa delta (marutam) and the coasts of the deep South (neytal).32 The sectarian commentaries link the coming descriptions with Veá¹ kaá¹eÅaâs preference for the South, and for the southern divya deÅas, holy places of pilgrimage, Indeed, the South and sacred places particularly dear to him form the core of the anticipated journeyâs descriptions. And there is a hint of internal scholarly critique. At one point (1.10), Veá¹ kaá¹eÅa refers to wild peacocks (vipinaÅikhinaḥ) struck dumb as the goose flies by, having lost their âeye-feathers in autumn,â the same birds who had prattled endlessly when the goose was far away on the peaks of KailÄsa. The verse conceals a Åleá¹£a, a double entendre: vipinaÅikhinÄá¹ can also refer to crude country Brahmans (sikhÄ refers to the traditional hair tuft) who prattle away when the most noble and learned among them are gone. ÅrÄ«vaiá¹£á¹ava tradition links this to Veá¹ kaá¹eÅaâs own experience: when he had gone on his pilgrimage to the North, say the commentators, corrupt South Indian Brahmans had made a grand show of themselves, only to fall silent upon his return.33

With 1.11 begins a richly figured series of descriptions of a landscape redolent with perfumes, of night-flowering red lotus and the kuvalaya blossoms that whirl about in the currents of the lakes, the honeyed sexual exudations of elephants in rut, and the air thick with the pollen of the red bandhujÄ«va flowers. In 1.12 we hit upon a perhaps unusual detail: a lovely iconic image of the god Åiva who bears both the crescent moon and the goddess Gaá¹ gÄ in his hair. The verse is a most elaborate upamÄ or extended simile based on red and white color, the Åleá¹£a or double entendre on each adjective, and another example of atiÅayokti, hyperbole, indexing RÄmaâs excessive mood and powerful emotional state. The goose is compared to the crescent moon on Åivaâs head, drowned in the waters of the Gaá¹ gÄ, reflecting the red-lac dye from the feet of his wife PÄrvatÄ«.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Universe of Us by Lang Leav(15055)

The Sun and Her Flowers by Rupi Kaur(14500)

Adultolescence by Gabbie Hanna(8907)

Whiskey Words & a Shovel II by r.h. Sin(7998)

Love Her Wild by Atticus(7740)

Smoke & Mirrors by Michael Faudet(6173)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5756)

The Princess Saves Herself in This One by Amanda Lovelace(4961)

Love & Misadventure by Lang Leav(4832)

Memories by Lang Leav(4788)

Milk and Honey by Rupi Kaur(4735)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4538)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4324)

Pillow Thoughts by Courtney Peppernell(4265)

Good morning to Goodnight by Eleni Kaur(4217)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4083)

Algedonic by r.h. Sin(4051)

HER II by Pierre Alex Jeanty(3596)

Stuff I've Been Feeling Lately by Alicia Cook(3441)